When we reject identity, what are we actually rejecting?

When the slogan of rejecting identity is raised, the stance often appears as a declaration of liberation from ready-made constraints, or an attempt to break away from predefined classifications. Yet this rejection, in many cases, does not target a clearly defined concept as much as it reacts to a vague perception that has accumulated over time. Identity is not rejected because it has been fully understood, but because it has been presented in collective consciousness as a rigid mold—one tied to a literal recall of the past and burdened with formal judgments that fail to reflect the reality of place or the transformations of society.

Here lies the core of the issue: when rejection shifts from a conscious critical act to a generalized reaction, it excludes the concept before questioning it and closes the discussion before its boundaries become clear.

How Was Identity Reduced to a Stereotype?

The distortion of identity did not stem from its essence, but from the way it was taught and represented over time. Rather than being understood as a flexible system of thought that responds to societal change, identity was reduced to ready-made images and repetitive formal elements, until it became synonymous in the public imagination with imitation or closure.

This reduction did not arise from conscious rejection, but from the accumulation of superficial practices that reproduced identity as a fixed visual template, detached from its social and economic context. Over time, identity shifted from being a tool for interpretation and understanding into a mental image that is automatically invoked—and automatically rejected—without distinction between the concept itself and the distorted representations attached to it.

Confusing Identity with History: The Beginning of the Crisis

The crisis of identity began when it was treated as a bygone time rather than an ongoing methodology. History, when invoked outside its context, transforms from a cognitive memory into a symbolic burden, and identity becomes a practice of retrospection unrelated to the present.

This confusion between what is historical and what is methodological hindered identity’s ability to evolve and caused it to be understood as a formal obligation to the past, rather than a living relationship with place and people. As this perception became entrenched, any discussion of identity began to be received as a call to move backward, not as an attempt to read the present. It is precisely here that the crisis took shape: when identity was detached from its time and understood as memory rather than as a thinking tool.

Identity as an Outcome of Contextual Awareness

Architectural identity is formed as a natural outcome of a design process that begins with an analytical reading of context and ends with the consolidation of architectural decisions. It emerges when design treatments are grounded in the deconstruction of an interconnected system of determinants, including climate, economic feasibility, usage patterns, and spatial relationships.

How can a medical prescription succeed without an accurate diagnosis? By the same logic, architectural decisions remain limited in effectiveness if they are not based on a precise understanding of site components and the nature of their interaction.

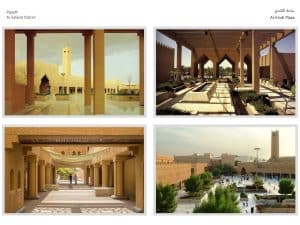

This approach was practically embodied in projects that tested the relationship between architectural form and spatial performance. In Al-Kindi Square, for example, the distribution of masses and the treatment of shading were calibrated based on analyses of pedestrian movement, solar exposure patterns, and thermal comfort requirements. This allowed an architectural language to emerge from the conditions of the place and the mechanisms of its use.

When design instead begins with a preconceived desire to “produce identity” in isolation from such understanding, it becomes an imposition of a ready-made model onto a different context.

Why Did “Non-Identity” Models Fail to Convince Their Users?

Some “non-identity” models presented themselves as neutral or universal solutions, capable of functioning in any context without direct attachment to place. However, this approach failed not because of the absence of local character, but because it assumed that formal neutrality could replace an understanding of surrounding conditions.

Buildings that ignored climate, operational costs, and daily usage patterns often appeared similar in form, yet were incapable of establishing a sustained relationship with their users.

Conversely, other projects—never presented as identity-driven—demonstrated greater acceptance and longevity because they adhered to contextual fundamentals and treated environment and economy as design inputs rather than secondary constraints. This clarifies that the problem does not lie in the absence of identity discourse, but in reducing the concept of globality to formal repetition that detaches projects from their reality and turns what is presumed to be a universal solution into a rootless experience.

When Does Rejecting Identity Become an Arbitrary Judgment?

Rejecting identity becomes a superficial judgment when evaluation is based on preconceived impressions rather than an actual reading of context. In such cases, projects are not questioned in terms of their relationship to place or their responsiveness to its conditions, but are immediately classified within ready-made binaries such as local versus global, or traditional versus modern.

This type of judgment does not result from a considered critical stance, but from the absence of an analytical framework that links form to function and context. When context is excluded from evaluation, critique shifts from a tool of understanding into an expression of taste or prevailing trends.

At this point, the problem lies not in identity as a concept, but in how it is invoked—or dismissed—without deconstruction. Identity is misunderstood once again, not because it is imposed, but because it is dismissed without recognizing what it represents: the relationship between design decisions and the place in which they operate.

What Do Environment and Economy Say That Form Does Not?

The limitations of form become evident when it is detached from the environmental and economic conditions from which it emerged. Architectural models do not function as neutral formulas, but as responses to specific contexts. When these models are transferred from one environment to another without reexamining their underlying conditions, their flaws are exposed, regardless of how refined their appearance may be.

This is evident in hotel or urban projects replicated from cold climates and applied to hot or tropical environments, such as some developments in Jakarta or the highlands of Al-Soudah. In these cases, the issue is not execution quality or brand identity, but the neglect of humidity, temperature, operational costs, and local usage patterns. The result is buildings that rely excessively on technical solutions, impose high operational burdens, and fail to establish a genuine relationship with users.

In contrast, other projects—often described as “global” in language—have succeeded because they were grounded in climatic understanding, calibrated their choices according to economic capabilities, and accounted for daily usage patterns. Here, environment and economy do not limit creativity; they provide the framework that gives it meaning. This is precisely the essence emphasized by the King Salman Charter for Architecture and Urbanism.

Technology Is Not the Opposite of Identity—It Is a Test of Awareness

Technology has never been the cause of identity loss, nor has it stood in opposition to it. The issue arises when technology is used as a ready-made solution to compensate for a lack of understanding, rather than as a tool built upon an informed reading of place.

Modern technologies, regardless of their efficiency, hold no inherent value; they derive meaning from the context in which they are employed and from the questions that precede their use.

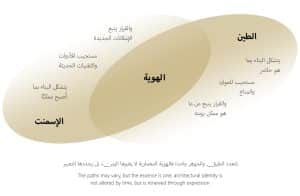

The shift from earthen construction to concrete, or from reliance on natural ventilation to mechanical systems, is not problematic in itself. It becomes so only when separated from its environmental, economic, and social implications. When technology is invoked to address the consequences of decisions not grounded in climate or usage understanding, it turns from a development tool into a masking device. The project is presented as advanced while remaining disconnected from its conditions.

In this sense, technology does not exclude identity; it reveals how identity is handled. It either extends a conscious methodology that balances modern capabilities with the requirements of place, or it becomes an indicator of the absence of such methodology. The question then is no longer about how modern the solution is, but about how aware it is—not about the quantity of technology used, but about its ability to harmonize with reality rather than impose itself upon it.

The Problem of Understanding in Identity Discourse

The challenge of identity in architectural practice is less a design problem than a reflection of a deeper flaw in understanding and education. When architecture is taught as a collection of formal solutions or isolated technologies detached from context, engagement with place becomes an exercise in visual adaptation rather than analysis.

In such cases, designers are not trained to read climate, economy, or patterns of living, but to select ready-made models and repackage them under different labels. This does not result in the loss of identity as much as it leads to its misinterpretation. Projects often accused of lacking belonging are not necessarily the outcome of deliberate rejection of context, but rather the product of practices that were never equipped with the tools to read place.

When these tools are absent, identity becomes a convenient scapegoat for methodological failures and is viewed as an obstacle rather than as an indicator of missing understanding. Thus, the debate around identity cannot be resolved without questioning the system that produces it. The issue does not lie in the diversity of environments or cultures, but in the designer’s readiness to understand and engage with them.

When this understanding is rebuilt on clear analytical foundations, the identity crisis recedes naturally, because it was never the root problem—it was one of its symptoms.

Understanding Context as a Professional Responsibility in Shaping Identity

From this perspective, design practice is not measured by the similarity of outputs or their formal affiliation, but by the methodology’s ability to respond to differing contexts. The designer is not tested by what is transferred from previous patterns or solutions, but by how effectively the conditions of a given place are deconstructed and translated into design decisions consistent with its environment and constraints.

Within this framework, understanding context and respecting its parameters become fundamental professional responsibilities—particularly when working outside familiar environments, where differences do not justify imposing ready-made models or ignoring local conditions. Identity, then, is neither borrowed nor imposed; it forms as a direct result of an informed reading of context and as a logical outcome of a design process that begins with understanding and ends with suitability.