How can architecture reflect its identity and historical roots, balancing authenticity and modernity in a rapidly developing urban environment?

Details Between Memory and Identity

In traditional architecture, details were never mere decorations; they were design solutions responding to the environment and way of life. The courtyard was not just an interior void but a space for cooling and gathering. The shaded corridor was a means of organizing movement and providing comfort. Ornaments were tools for controlling light and privacy. These elements together formed a clear architectural identity and established a direct relationship between the building and its community. Today, when such elements are reduced to superficial facades without real function, architecture loses its sincerity — and with it, the visual memory that gives a city its character and uniqueness.

When Architecture Loses Its Context

When architecture is detached from its context, it loses its authenticity. What may seem like a mere difference in form leaves a profound impact on both the urban fabric and the people. A building transplanted from its native environment to another may look familiar, but it fails functionally: a glass façade in a hot climate consumes massive energy, and a Hijazi model in Najd or a Najdi one in Asir quickly collapses under environmental pressures. Thus, identity is not a mold to be replicated, but a system conditioned by climate, customs, and materials.

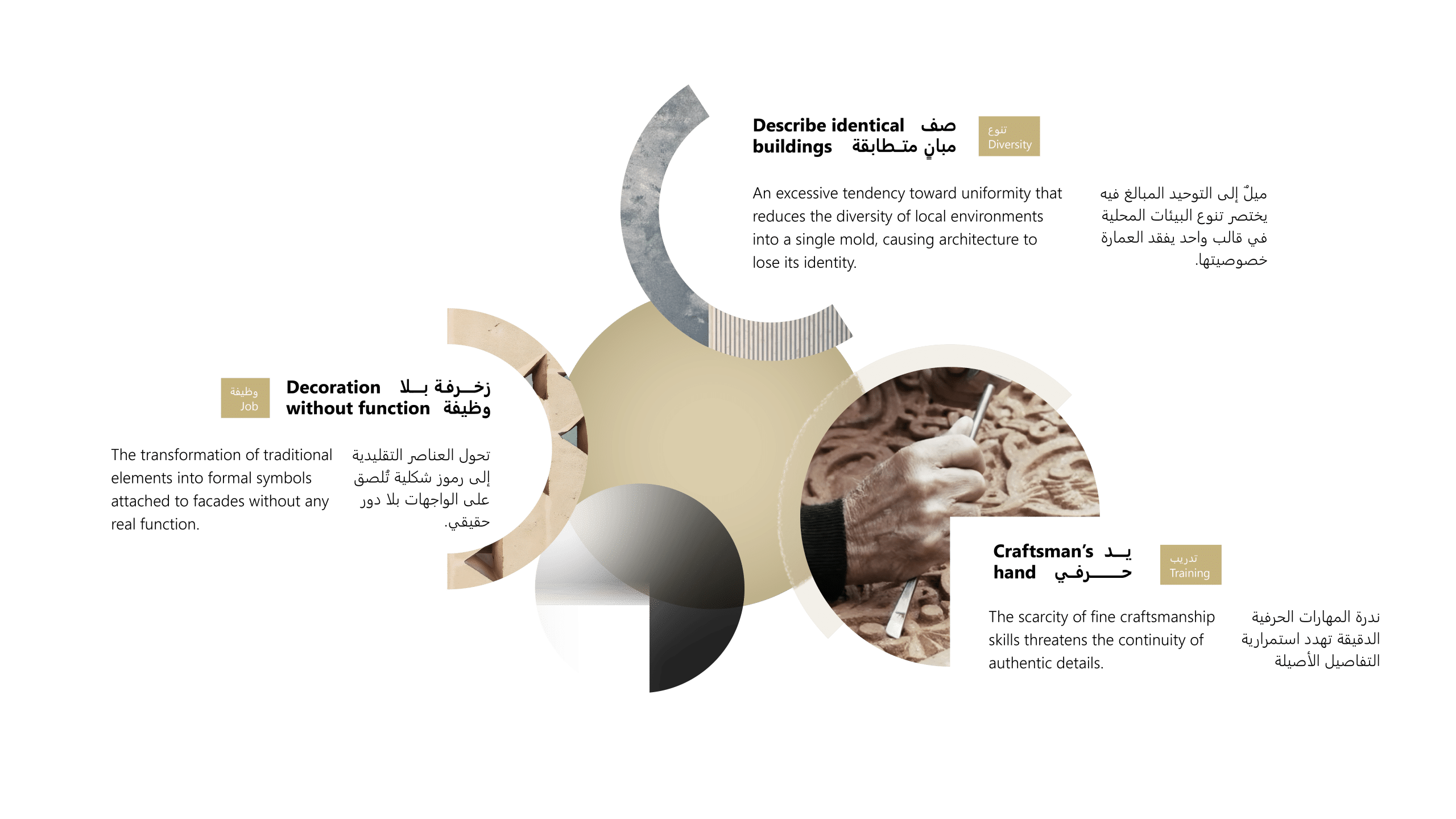

Challenges and How to Address Them

Rooting architecture cannot remain a slogan; it requires conscious practice facing several obstacles. One of the most critical risks is turning traditional elements into mere symbolic ornaments attached to facades without functional roles. Another challenge is excessive uniformity, where the diversity of local environments is reduced to a single template, stripping architecture of its distinctiveness.At the implementation level, the scarcity of skilled artisans threatens the continuity of authentic detailing. Still, solutions exist when each element is tied to its function, diversity is allowed within thoughtful parameters, and investment is made in training craftsmen and documenting their methods. Only then can rooting shift from an idealistic notion to a sustainable practice.

Reviving Urban Memory – The Salmani Architecture

Salmani architecture presented a clear model for reinterpreting urban identity. It did not reproduce heritage as fixed templates, but reimagined it to serve modern needs. It centered design around the human being — with human-scale proportions, well-studied circulation, and spatial comfort both climatically and visually. It adopted core principles such as moderation, simplicity, privacy, and hospitality, translating them into practical solutions: spatial gradation from public to private, shaded walkways encouraging pedestrian movement, majlis spaces reflecting social values, and massing that reduces heat loads. Projects like Qasr Al-Hukm and Al-Kindi Plaza embodied this approach — not replicating the past but shaping a contemporary urban environment inspired by place and responsive to society’s needs.

When Architecture Regains Its Context

Architecture is not measured solely by the beauty of its façade but by its ability to integrate with its urban fabric. When context is restored, elements return to their natural function: the courtyard becomes a ventilation and social system, stone transforms from mere material into a constructive element rooted in the land, and colonnades evolve from repetitive shapes into extensions of pedestrian pathways.This return to context grants cities clarity in their features, reduces operational costs, and renews people’s sense that the place was designed for them. Here, identity is neither borrowed nor symbolic — it is shaped by the living relationship between architecture, human, and city.

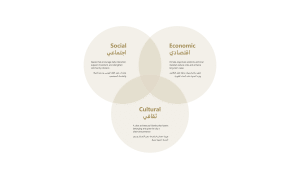

Dimensions of Impact

The true impact of context-aware architecture goes beyond aesthetics; it appears in the city’s performance and community behavior. Socially, it creates public spaces that foster daily interaction and movement, strengthening social cohesion. Economically, climate-sensitive design and local materials reduce maintenance and operating costs, making buildings more sustainable long-term. Culturally, a coherent architectural identity reinforces self-confidence and offers cities a distinctive image locally and globally. Through these three dimensions, architecture transforms from isolated buildings into an urban practice that directly enhances sustainability and belonging.

Architectural Examples

The urban identity is clearly reflected in the experience of the King Abdulaziz Historical Center in Riyadh. The project was not about constructing new buildings but reconfiguring an integrated urban scene: linking Qasr Al-Hukm to the city through interconnected courtyards and pathways with a thoughtful transition from public to private spaces. The architectural masses balanced traditional features like walls and towers with modern technologies ensuring efficiency and sustainability. This approach avoided nostalgic imitation and instead created a cohesive urban system that restored clarity to the city and offered lively spaces for the community.

Similarly, the initiative to restore 130 heritage mosques represents an advanced level of project management. It was not based on beautification or symbolic revival, but on rigorous documentation, material selection, and detailed restoration ensuring structural integrity and sustainability. This initiative demonstrates that architectural heritage is no longer viewed as a relic of the past, but as an active contributor to shaping Saudi urban identity.

Architecture and Its Roots in Transformation

Architectural history shows that innovation does not disconnect from memory. The details that endured for centuries — from courtyards and shaded corridors to wind catchers — were not ornamental but practical solutions that predated modern sustainability concepts, reflecting deep understanding of climate and human movement. Mosques and squares served as anchors connecting neighborhoods to the wider community, weaving daily life harmoniously with environment and urban form. Today, architectural identity can embody this rooted essence to confront modern challenges — rapid growth, social and economic shifts, and environmental sustainability. Engineering methodologies remain essential tools for reflection, understanding, and preserving cultural continuity in cities that constantly evolve.